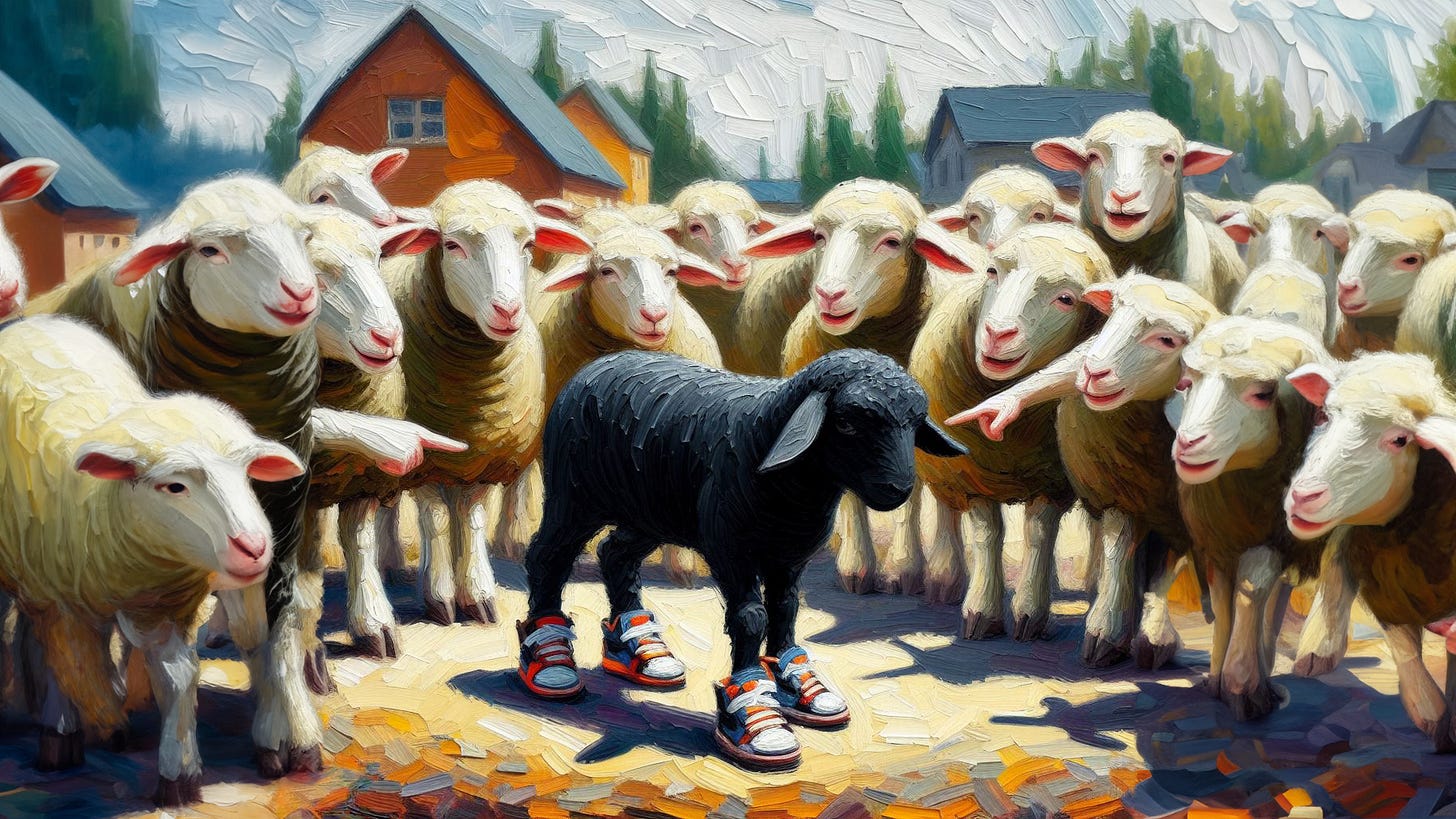

"Blackness” Is a Collectivist Control Tactic—Even A Child Could See It

With every lame comment about how “white” I dressed or talked, it weakened my resolve for pursuing other people’s acceptance.

As a child, I never felt like I was “enough.” I wasn’t enough to keep my father involved in my life, I wasn’t confident enough in myself, and I wasn’t black enough for anyone’s standards.

I’ve never kept up with anyone’s standard of blackness, regardless of whether they were white or black, throughout my life. When I lived in the suburbs and rural areas, it wouldn’t be uncommon for me to be referred to as “White Adam” by some of my white classmates followed by a jovial laugh. I was the punchline of the moment but with every lame comment about how “white” I dressed or talked, it weakened my resolve for pursuing other people’s acceptance.

When I lived in neighborhoods that featured more children who looked like me, I didn’t quite fit in with them either. However, instead of mocking me, they often distanced themselves from me.

I lived in four states before the age of 18, and every time you move you must start over with gaining acceptance and galvanizing new friendships. The older you get, …